The following transcript is from a homily given in Christ Chapel at Gustavus Adolphus College (St. Peter, MN) on October 13, 2014. As part of the faith and learning series in Daily Sabbath, the text for the day was Luke 15:11-32. The audio recording can be found at 8:45 on the below link:

Let us pray. For all those who see home disappear behind them; For all those who cannot see home ahead of them; For all those who yearn for home around them; Help us to see, O God, in the struggle of your people the presence of your prophets and a path for ourselves. Amen.

Let us pray. For all those who see home disappear behind them; For all those who cannot see home ahead of them; For all those who yearn for home around them; Help us to see, O God, in the struggle of your people the presence of your prophets and a path for ourselves. Amen.

First and foremost, I wish to proclaim publicly a Happy 4th Birthday to my son, Khaya, who was brought into this world on October 13th in the year 2010 at Parklands Hospital outside of Durban on the east coast of South Africa. My prayer for my son today is the same as it was on his first day, as I ask God to ensure that my nature and my nurture helps him more than it hinders (only time will tell!).

As I ponder more specifically surrounding the significance of this day, and as I remember the thoughts and emotions of four years ago surrounding what it would mean to welcome a child into the world half-way across the world, I recall then – as I do now – that such global movement is by no means outside the norm in our so called global village. The fact of the matter is that the birth of my own son 10,000 miles away from this place is a reminder that the human community does indeed exist in a perpetual state of motion, as various forms of human migration are a constant feature of our local and global reality.

According to the International Organization for Migration, the total of international migrants increased from an estimated 150 million in the year 2000 to about 214 million in 2010, and the number of internal migrants who move within the borders of a given country is now over 750 million per year. Yes, we as human beings are migratory people because we are indeed people on the move.

However, unlike the so-called first-world reasons that led to my moves, most global relocations are often related to so-called third-world realities, such as, the harsh consequences of warfare, environmental destruction, and gross inequality resulting from economic dysfunction. As a result, those most often engaged in migration often do so not to fulfill life-long dreams of seeing the world, but most people move simply to see more of life. In other words, most people on the move are not trying to see if the grass is greener on the other side of the fence, but they move because there is simply no grass left on their side.

This is the sad reality of our world, especially for those without the power and privilege necessary to build the fences in the first place.

But of course, this phenomenon of migration as a whole is by no means exclusive to the present, as human migration has existed for thousands of generations, and as a result, thousands of stories have been told about its conditions and consequences. For example, the New Testament passage from Luke’s Gospel often known as “The Parable of the Prodigal Son” includes some of the harsh realities often associated with migration. As a result, one can examine this well-known parable through the lenses of migration, and in doing so, receive insights into how we can more faithfully live in this increasingly interconnected global village.

As Luke’s Gospel reminds us in Chapter 15, verses 11-32, the youngest of two sons asked for an early inheritance from his father, received it, and then traveled to a “distant country” where he “… squandered his property” in what the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible translates into English as “dissolute living.” As the term “dissolute” typically intends to describe degenerate and/or sinful behavior, we often conclude that the youngest son was deeply immersed in an immorality that puts even our most graceless students to shame. Which means, we find it quite difficult to feel sympathy when this son later falls into the depths of poverty.

Whether we are willing to admit it or not, we tend to perceive the so-called prodigal son as someone who simply got what he deserved in the spirit of retributive justice, like a divine criminal karma. As the parable seems to illustrate, not only did this youngest son waste the inheritance, but he seems to have done so through choices that brought deep dishonor to his family. While the New Revised Standard Version uses “dissolute” to describe the younger son’s behavior, the King James Version uses the term “riotous”, the Revised Standard Version describes it as “loose” and perhaps my favorite, the New International Version offers the term “wild”.

But all of these word choices fall short. As every English translation of the Bible is essentially an english interpretation of the Bible, there are times when the English words on the page are simply wrong. In verse 13, the interpretation – and therefore the translation – is just that. Wrong. The Greek word originally used in Chapter 15 verse 13, asōtōs, actually means “expensive” or “without saving” – which not only has nothing to do with our common conceptions of morality, but it also just so happens to describe the far majority of people on this campus! The text simply reveals that the second born son simply did not save his funds properly, which means, the accusations surrounding prostitution made against him in verse 30 are not grounded in any textual evidence whatsoever, which leads us to believe that the older (and spiteful) brother simply made it up in order to influence their forgiving father. In other words, while we often like to believe that the youngest son was fully deserving of his impoverished predicament, upon further review, Luke’s Gospel does not confirm or deny anything about the younger son spending the inheritance through immoral means. As a result, while the younger son should be held accountable for his lack of fiscal discipline, we should recognize that factors outside of his personal decision-making skills may have led to his impoverished state. In summary, his poverty was not simply about choice, but it was also about circumstance.

As Luke’s Gospel shares in verse 14, “… a severe famine took place throughout the country,” which shows an economic dysfunction related to an ecological crisis that surely had an impact on those most vulnerable, such as foreign migrants. Furthermore, we also learn of the youngest son being taken advantage of in verse 15 by an exploitative employer who recognized the opportunity to profit from a non-unionized and ultra-vulnerable foreigner employee that could be paid less than a living wage. Does this sound familiar yet?

Ecological crisis.

Economic disfunction.

The exploitation of migrant labor.

As Mark Twain said, history does not repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme. Which is why, this parable is not merely about a prodigal son, but this text is about a prodigal public. A prodigal public. A prodigal public that did not care for a vulnerable and lonely immigrant stranger, for as we read in verse 16, when the youngest son was at risk and in need, “… no one gave him anything.” No one gave him anything, or as we hear today as thousands of unaccompanied children continue to struggle on the southern border of this country: “Not my child. Not my problem”.

Now that is the definition of dissolute living.

And so, to conclude where I began, with the birth of my first child. When my son was born in Durban four years ago today he spent his first eight days of life in the intensive care unit as Kristen and I struggled to respond to some of the complications that were presented to him and us. At first I remember thinking that we were a long way from home, and I remember wondering if I had put my child at risk and questioning whether or not we should have traveled back across the ocean for his birth. However, at that time in which I was as lonely and vulnerable as ever before, as the life of that which I loved the most was in the hands of our local hosts, my wife, myself, and my new son received a level of grace and hospitality that reminded us that we were indeed at home all along. We were home. Four years ago, as my son struggled during his first days of life, in what was some of the darkest days of my life, at a time in which I was a vulnerable and lonely foreigner at the mercy of a local community, we were shown that the grass is never greener on the other side when you are among people who refuse to build fences.

Thus my son’s name, Khaya. K.H.A.Y.A. An isiZulu word from South Africa which literally means “home”. A name given to him exactly four years ago today in order to remind him, his parents, and everyone he meets, that no matter where you are, and no matter what you have done or left undone, and no matter the color of your skin or the color of your passport, you are always surrounded with the love of God found in Jesus Christ. Which means, that you – and everyone else around you – are always home, because of that radical promise of the presence of God. The promise that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus. The promise of the Gospel.

And so, with all of these thoughts in our mind, not only are we reminded of the profound grace of God in making this Earth our home, but in doing so, we are shown our sacred responsibility to have a preferential option for the immigrant, because that is the commitment of the Christian, and quite frankly, should be the commitment of this college: The confession that the children of others are the children of us. Why? Because our core and inherent unity as human beings takes full precedence over national identity, ethnic heritage, and/or economic self-interest, and the result of such radical hospitality is a sacred society that is more willing to advocate for others rather than expose and exploit others.

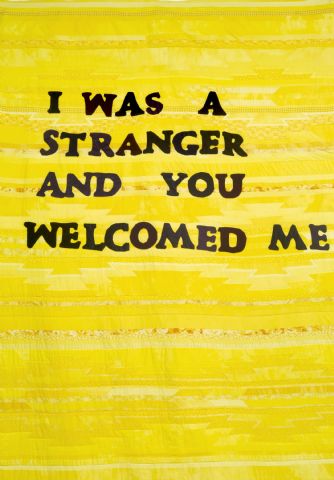

And so, as the pathetic public political debate rages on in this country, the Gospel speaks loud and clear about an immigrant incarnate of God who died on a Cross. And this immigrant incarnate reminds us, that instead of living as a prodigal public that too often wastes the hopes and dreams of those seeking a better life, and instead of putting up more fences to ensure the green grass stays on our so called side, in response to the grace of God that knows no borders, we are called to continue to welcome the various strangers of our world into our midst, extend the radical hospitality of Jesus, and in doing so seek to restore communities into the redemptive vision that God has placed before us.

So all may have the joy of being at home.

So all may experience life in its fullness.

So all may have a present day taste of such amazing grace.

May we recommit ourselves to this call as God in Christ continues to recommit to us.

For all those who see home disappear before them…

For all those who cannot see home ahead of them…

For all those who yearn for home around them.

May God help us to see in the struggle of others, the presence and a path, for a ourselves.

Amen.

The Rev. Brian E. Konkol serves as a Chaplain of the College at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minn. An ordained pastor of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), he holds degrees from Viterbo University (La Crosse, WI), Luther Seminary (St. Paul, MN), and the University of KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa). He blogs at http://briankristenkonkol.blogspot.com and tweets @BrianKonkol