* The following text is taken from a homily given in Christ Chapel, on the campus of Gustavus Adolphus College (St. Peter, MN), on February 7, 2017. Please note that the below manuscript was written with the intention to be heard, not read, thus the various grammatical choices were made with an emphasis on the ear, not the eye.

* The following text is taken from a homily given in Christ Chapel, on the campus of Gustavus Adolphus College (St. Peter, MN), on February 7, 2017. Please note that the below manuscript was written with the intention to be heard, not read, thus the various grammatical choices were made with an emphasis on the ear, not the eye.

—

When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them. The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the Lord your God (Leviticus 19:33-34, NIV).

The Spring Semester has begun, this is Day Two, January is now behind us, and the twelve days of Christmas are long past.

However, while most Christmas decorations are down, the deeper meanings of Christmas remain to this moment, as the wider implications of the incarnation most sure persist.

During the Christmas Season, the 1st Chapter of John’s Gospel reminded us that the Word became flesh and dwelt among us. The World became flesh, and dwelt among us, as a child. And during this Season of Epiphany and beyond, we are reminded that it was not just any child born in Bethlehem, but it was a particular child. It was a particular child born at a particular time and in a particular place. For when Jesus arrived, this Son of God did so as a vulnerable infant who must spend his first vulnerable days being cared for by two vulnerable parents, struggling within a vulnerable situation. Jesus begins his life not in a home or a hospital or even a discount hotel, but as the 2nd Chapter of Luke’s Gospel reminds us, God breaks into the realities of our world through the broken harsh reality of an improvised – and impoverished – makeshift shelter, for there was no room for him at the inn.

The Word became flesh, and dwelt among us, as an outsider, an unknown, and as a social outcast.

As the 2nd Chapter of Matthew’s Gospel reveals to us, Jesus arrives into the world as part of a family who must quickly flee their familiar land. They must flee because they are threatened by a crusade of terror ordered by the sinister King Herod. And because of this vile and imperial tyrant, Jesus is left transported into a foreign land, through the desperate and difficult migration into Egypt.

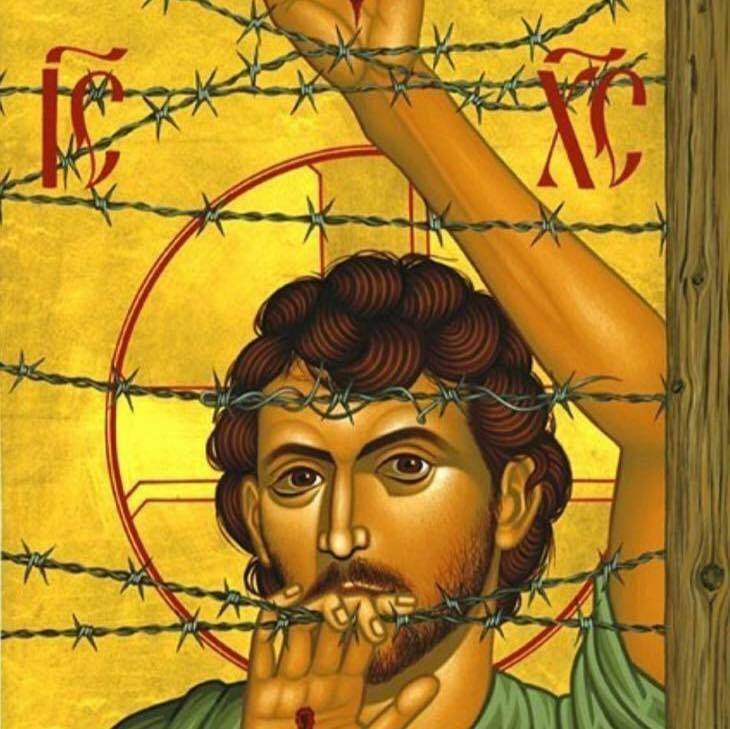

The Word became flesh, and dwelt among us, as a refugee.

As one who was forced to leave his familiar surroundings in order to escape extreme persecution at the hands of a disturbing demagogue, Jesus was – by definition – a refugee. Jesus was both divine and undocumented, and such status should capture our collective attention, especially in times such as ours.

As we review the overarching narrative of the Bible, we recognize that Jesus’ refugee status was no minor detail, and thus no inconsequential side-note in our pursuit of theological understanding. On the contrary, Jesus’ immigrant identity is the opening note in the existential song that would become his life and his ministry. And at the same time, Jesus’ migratory character is a clear echo of the larger scriptural symphony that begins in the Book of Genesis. For that young refugee named Jesus grows into a respected teacher, well acquainted with the Hebrew scriptures, with its often-repeated refrain to welcome the foreigner, such as today’s preaching text from Leviticus:

When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them. The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the Lord your God (Leviticus 19:33-34, NIV).

As a Jewish Rabbi, Jesus would have known such a text, as well as countless other migration stories. Jesus would have known about Adam and Eve, who were expelled from Eden, their homeland. He would have read about Noah and family, who were adrift without a destination. He would have heard about Sarah and Abraham, who were mandated to migrate. And of course, he would have known about the ways in which God’s people wandered for years through their collective exodus out of slavery and through their journey to the promised land. In total, Jesus himself was immersed in a sacred Hebrew text that repeatedly told migration stories and consistently called upon the people of God to promote hospitality and concern for the strangers in their land.

And so, because he was immersed in stories about migration, and because his own story was one of migration, it should be no surprise that Jesus spoke over and over and over again about hospitality to foreigners. Furthermore, it should be no surprise whatsoever, that according to the Gospel of Matthew, in Chapter 25, following three years of walking, talking, teaching, and healing, when Jesus concludes his ministry with one final lesson, he uses such precious moments to offer a message that puts the premium on whether or not we serve the so-called “the least of these” by “feeding the hungry,” “clothing the naked,” and welcoming the stranger in our midst.

As he journeyed toward the cross, it is as if Jesus wanted to share once more, “The Word became flesh, and dwelt among us, as a refugee. So if you’re looking to dwell along God, you’ll find God among the most vulnerable, you’ll find God among the most marginalized, and you’ll find God among the most exploited and the most ignored.” Or, in other words, “If you’re looking for the face of God in our world, you’ll most likely find it on the OTHER side of the border walls we so often seek to build.”

And so, for people who identity as followers of Jesus in the here and now, we recognize that not only was he a refugee 2,000 years ago — but, Jesus is a refugee, today.

Jesus was, and is, a refugee, because we see the face of God most clearly in the faces of those whose lives most resemble the life of Christ in our day and age. We see Jesus is the undocumented divine. The holy families of our time. Those seeking safety. Those seeking shelter. Those seeking care. The Word of God made flesh is present in each and every person who begins that long trek away from the economic, political, and social unrest of their homes. Jesus is present alongside each and every pregnant mother who defies the odds of physical and emotional dehydration. Jesus is present alongside each and every child that is more than ready to delight in a better future. And Jesus is most fully present alongside each and every tireless officer, case manager, and beloved volunteer who greets the stranger with open arms and compassionate hearts, as if they were meeting the Risen Christ himself.

So what does this mean? So how do we, today, here and now at Gustavus Adolphus College, as members of a college community founded by immigrants, go and do that which Christ calls us? How do we practice the radical hospitality so often cited in Scripture? How do we restore communities by resisting exclusion to name and claim diversity, equity, and embrace? How do we follow the path of Jesus by accompanying those whom Jesus would walk with today?

Perhaps the best insight to which we could do in the here and now, comes to us by returning to where we began, with the Christmas story itself.

In the 2nd Chapter of Matthew’s Gospel, when King Herod learns that a threat to his power was born in Bethlehem, he subsequently orders all male infants under the age of two in and around the area to be killed. This is, of course, a segment of the Christmas story that we so often seek to suppress while cozy and content with our gifts around the Christmas tree. Yet, what we should not suppress, is the lesson we learn from the so-called “Wise Men” of the story, those whose wisdom is made most known by defying the power-obsessed earthly authority of their day, an authority that has completely lost his mind.

In Chapter 2, verse 7, the “Wise Men” are confronted by King Herod, whom scripture characterizes as a narcissistic, insecure, lying, power-hungry, socio-path. And when this plutocratic manipulator learned that a threat to his power was born, he seeks to protect his power at all costs. But of course, when Herod tries to enlist the cooperation of the Wise Men in trying to detain and destroy Jesus, the wise men resist. And because of such prophetic resistance infused with holy wisdom, Jesus is allowed to live.

Scripture tells us that these “Wise Men” visited Jesus after his birth and bore gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. Yet their greatest gifts were offered when they exercised wisdom and bore their own faith at the feet of Christ. For instead of uncritically obeying the horrific order bestowed upon them by the insecure and insidious King, the wise men wisely followed the light of God. And in following the light, they resisted the darkness, and Jesus lived.

The Word became flesh and continues to dwell among us.

May we follow the light and resist the darkness.

So Jesus might continue to live.

So we might continue to live.

Amen.

—

The Rev. Dr. Brian E. Konkol serves as Chaplain of the College, teaches in the Peace, Justice, and Conflict Studies program and Three Crowns Curriculum, and is the Creative Director for Christmas in Christ Chapel at Gustavus Adolphus College. He tweets @BrianKonkol and blogs at http://briankristenkonkol.blogspot.com

NOTE: The views expressed here are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Gustavus Adolphus College, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, or other affiliated organizations. Those with questions or concerns may contact the author.

NOTE: This sermon utilizes thoughts expressed by the leaders of Christian Theological Seminary (Indianapolis, IN), “Statement Condemning the Immigration Ban” http://www.cts.edu/about-cts/statement-condemning-the-immigration-ban.aspx